Die ägyptische Göttin Taweret als Amulett

- By Galerie Alte Römer

- 7 Dec 2016

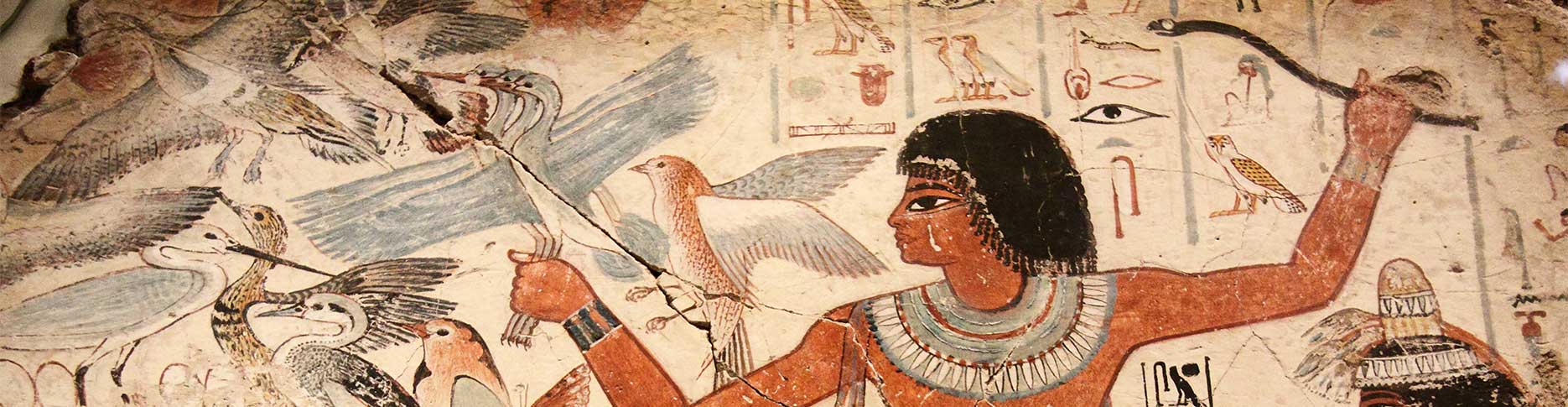

Beispiel für ein originales ägyptisches Amulett der Taweret:

Ägyptisches Amulett der Taweret aus der Spätzeit

Der Papyrus als Amulett symbolisiert Gedeihen (wie die Pflanze) und Jugend. Ein solches Amulett konnte als Schmuck im Alltag getragen werden oder einem Verschiedenen beim Bestattungsritual um den Hals gelegt werden (vgl. Totenbuch, Kapitel 159).

Diese Amulettform war in der Zeit der 26. bis 30. Dynastie verbreitet, als die ägyptische Schlangengöttin Wadjet am meisten verehrt wurde. Die Transkription ihres Namens ist identisch mit der des Wortes Papyrus. Die Papyruspflanze ging laut einem Pyramidentext aus dieser Göttin hervor, wodurch der Papyrus mit dem nördlichen Teil von Ägypten in Verbindung gebracht wird.

Beispiele für ägyptische Amulette in Form eines Papyruszepters:

Ägyptisches Amulett in Form eines Papyruszepters

Literatur zu ägyptischen Papyrusamuletten:

C. Andrews, Amulets of Ancient Egypt, S. 81f.

A sphinx is a mythical creature deeply rooted in the culture of Ancient Egypt. The body is that of a lion, the head can be of a human, falcon or ram. Before the Greek adaption of the myth sphinxes were mostly depicted without wings (for an early example with wings see e.g. the scarab from the time of Hatshepsut in Petrie, Historical Scarabs, fig. 29, 889). In art, sphinxes are shown standing, seated or walking. The origin of the myth is not known.

Earliest known sources suggest the sphinx represents royal status and power of the Egyptian pharaoh. As a motive on scarabs, the creature was made popular by the Hyksos. During the New Empire, it was already a mass product with countless variations of the main theme. Two main scenes can be distinguished. A sphinx facing and fighting evil, e.g. in the symbolic form of a cobra. Or a sphinx facing and representing good, e.g. in the form of the Ankh symbol of life. In both cases, the scarab amulet should magically protect the one owning or carrying it.

Stone idols spread across the eastern Mediterranean during Bronze Age. There are various different types. But they all share a strong abstraction of the human characteristics. That is why they have been widely ignored as “primitive art” during the 19th century. But with the rise of Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th century Bronze Age idols have been declared an ancient ideal for Modern art.

Here is an example from ancient Anatolia, the modern state of Turkey. The so-called Kusura type idol dates to the 3rd Millennium BC. It is made of white, finely crystalline limestone. The famous archeologist Heinrich Schliemann had one of those idols in his collection as early as the late 19th century.

Kusura-type idol